Unicode Notes

References

Unicode

After the mess of codepages and DBCS, Unicode was an effort to create a single character set - Unicode isn't simply a 16-bit code where each character takes 16 bits and therefore there are 65 536 possible characters - that's not correct!

Code point is represented in the format U+0283, the latter is in hexidecimal and is called a code point. There's no real limit on the number of letters that Unicode can define since it doesn't need to be squeezed into two bytes!

Unicode is a computing industry standard for the consistent encoding, representation, and handling of text expressed in most of the world's writing systems. For future usage, ranges of characters have been tentatively mapped out for most known current and ancient writing systems.

Example

"Hello"

U+0048 U+0065 U+006C U+006C U+006F.

the first 2 hexadecimal of the code points

refers to the Unicode PlaneStoring Unicode

Unicode encodings define how they are stored - the format. From the above example

There are many ways of encoding Unicode, a few include:

UCS-2 (2 bytes)

UTF-16 (16 bits)

UTF-8 (8 bits)

UCS-2

Store all characters a two bytes. For some, this was unpopular since computing originated with American roots thus English was their primary concern. This inevitably led to the question why do we need to waste 2 bytes to store a character.

As a consequence, because its 2 bytes are read as a single code point value, it can only represent 216 code points - Basic Multilingual Plan (BMP) are the only code points it can represent.

UTF-16

An extension of UCS-2 and can encode 220 code points (16 planes). This is due to its variable-length encoding as code points are encoded with one or two 16-bit code units, this means a character can be stored as 2-4 bytes. The byte order (endianness) is specified with the BOM which was considered wasteful and led the the birth of UTF-8. It is still used internally by systems such as Windows, Java and Javascript.

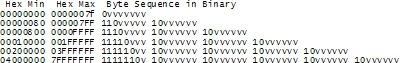

UTF-8

It could be store in 8 bits for <= 128 else be 2-6 bytes. This was more than sufficient to cater for all other languages' code points. Because of its variable length - it can encode up to 231 code points even though the current Unicode version has 6 planes with assigned code points.

The beautiful thing about UTF-8 is that it is compatible with the earlier character sets - ASCII, ANSI and OEM character sets!

Displaying Unicode strings

Once an encoding is selected, there needs to be a standard way of preserving this information so that programs displaying those strings can decode it correctly.

Email

Expected to have a strings in the header of the form: Content-Type: text/plain; charset="UTF-8".

Web

Joel CEO of Stack Overflow puts this bit really well:

For a web page, the original idea was that the web server would return a similar Content-Type http header along with the web page itself — not in the HTML itself, but as one of the response headers that are sent before the HTML page.

This causes problems. Suppose you have a big web server with lots of sites and hundreds of pages contributed by lots of people in lots of different languages and all using whatever encoding their copy of Microsoft FrontPage saw fit to generate. The web server itself wouldn't really know what encoding each file was written in, so it couldn't send the Content-Type header.

It would be convenient if you could put the Content-Type of the HTML file right in the HTML file itself, using some kind of special tag. Of course this drove purists crazy… how can you read the HTML file until you know what encoding it's in?!

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8">

</html>But that meta tag really has to be the very first thing in the

<head>section because as soon as the web browser sees this tag it's going to stop parsing the page and start over after reinterpreting the whole page using the encoding you specified.What do web browsers do if they don't find any Content-Type, either in the http headers or the meta tag? Internet Explorer actually does something quite interesting: it tries to guess, based on the frequency in which various bytes appear in typical text in typical encodings of various languages, what language and encoding was used. Because the various old 8 bit code pages tended to put their national letters in different ranges between 128 and 255, and because every human language has a different characteristic histogram of letter usage, this actually has a chance of working.

It's truly weird, but it does seem to work often enough that naïve web-page writers who never knew they needed a

Content-Typeheader look at their page in a web browser and it looks ok, until one day, they write something that doesn't exactly conform to the letter-frequency-distribution of their native language, and Internet Explorer decides it's Korean and displays it thusly, proving, I think, the point that Postel's Law about being “conservative in what you emit and liberal in what you accept” is quite frankly not a good engineering principle. Anyway, what does the poor reader of this website, which was written in Bulgarian but appears to be Korean (and not even cohesive Korean), do? He uses theView | Encodingmenu and tries a bunch of different encodings (there are at least a dozen for Eastern European languages) until the picture comes in clearer. If he knew to do that, which most people don't.

History

When Unix was being invented, we only needed to worry about unaccented English letters - this code was called ASCII and every character could be represented with a number between 32-127. Only 7 bits would be needed and therefore the 8th bit was extra.

The 8th bit was often used for control characters and so on. However the OEM character set that was used in the IBM-PC and was eventually codified in the ANSI standard. Everything below 128 was basically ASCII whilst anything greater used code pages e.g. Israel DOS used code page called 862. This was restricted per computer, so you couldn't usually have multiple code pages on a computer!

In Asia, their alphabets have thousands of letters and couldn't fit in 8 bits! This was usually solved with DBCS (Double Byte Character Set) where some letters were stored in one byte and others two. Windows' AnsiNext and AnsiPrev were functions to move forward and backwards (the latter near impossible). In some ways, this was a crude version of Unicode UTF-8!

Last updated